Tlatelolco Marketplace: Reputation systems have long underpinned confidence in economic exchange and reinforced prosocial behavior. (source: Wikimedia Commons)

by Joseph Knelman

In part, reputation systems have been central to the evolution of cooperation. Biology has revealed how organisms benefit from associating with cooperative counterparts and keeping track of previous behavior: Vampire bats, for example, remember individuals in their roosting group that share food in stressful times and will repay the favor according to this history of behavior. In humans, these tendencies to cooperate and remember actions have resulted in important reputation systems.

Increasingly, UX design must consider how to foster community interactions among users in the context of social networks (Facebook), sharing economies (Airbnb), and/or content creation (YouTube), for example. Currently, whether such online “communities” actually build demonstrable prosocial behavior is variable (and perhaps even result in the opposite effects). For companies where prosocial values are central to their business, UX Design faces great challenges (but incredible opportunity) in building environments where collective interests may be reinforced.

Social Feedback and Reputation

For online marketplaces and experiences in the sharing economy, reputation systems have proven central to prosocial behavior. Largely beginning with eBay in 1995, social reputation systems built on ratings and feedback (e.g. in Airbnb, Uber, Amazon Marketplace, Etsy, etc.) have allowed individuals of uncertain identity and disconnected locales to interact in economic exchanges with great confidence.

Reputation systems are powerful in reinforcing prosocial behavior as positive reputations garnered through constructive social interactions are associated with greater respect and cooperation, greater influence in a community, and greater likelihood of being included in exchanges (Simpson and Willer 2015). Tied to these benefits and intrinsic motivation, people will take on the costs associated with sharing reputation information for the betterment of others (Simpson and Willer 2015). In online marketplaces such as eBay, research has shown that the number of positive seller reviews impact both sales and selling price, and users (60-80%) are keen on sharing feedback, demonstrating benefits of good reputation in online contexts as well (Diekmann et al. 2014).

Design Considerations for Online Reputation Systems: Structure, Function, and Biases

Typically in online contexts, cumulative positive reputation systems are employed as users can easily escape negative reputation systems by changing identities. However, research has demonstrated that in online environments biases surrounding positive reputation systems inflate seller reputations due to fear of retaliation or a sorting effect, in which users submitting positive reviews act more readily to do so because they gain greater utility than those submitting negative reviews. In situations where online economic transactions are accompanied by more extensive social interactions, empathy may too stifle honest reviewing of a product. In total, truthful negative feedback is often omitted from reviews (Tadelis 2016, Fradkin et al. 2017). For example, research surrounding Airbnb’s reputation system showed that monetary incentives to submit feedback resulted in lower average ratings than the control, which was attributed to the incentive overcoming a sorting effect (Fradkin et al. 2017). How and when the design of a reputation system allows for such bias must be carefully considered, or else such bias may undermine user trust in the system itself.

The design of a reputation system can have important implications in the functionality and biases associated with the system. For example, feedback can be one-sided or two-sided, which may affect the nature of interactions. Many online social feedback systems are two-sided when both sides’ reputations are important to the transaction, but this design may also result in fear of retaliation. Anonymity or one-sided approaches may alleviate common biases against negative reviews, but this may also alter norms around the honesty of reviews. Requiring both parties to submit before making ratings public may also influence behavior. For example in a experiment with Airbnb’s reputation system, when a simultaneous reveal was implemented, the review rate for users on both sides increased and spikes in private feedback suggested greater honesty via a reduced fear of retaliation (Fradkin et al. 2017).

Qualitative reviews might also serve to build a reputation based on more complex feedback in place of ratings. On the Airbnb platform, one study found that the number of reviews was more strongly predictive of room sales than the rating score itself, which posits the possibility that reviews outside of ratings could also form the basis of a reputation system. Additionally, two-sided interactions may be intentionally incongruous to the extent that the rating system is different for the buyer and seller. In Airbnb’s experience platform, for example, the buyer may rank sellers on a 5 star rating system, while the seller (host) may simply give a thumbs-up or thumbs-down review of the buyer. Such incongruous feedback allows for valuable feedback on a product but reduces posturing for reciprocity of reviews since ratings cannot be tit for tat. These types of incongruities (others might include rating different categories, for example) are interesting considerations that may impact bias and the honesty of feedback in a positive reputation system.

The actual rating metrics that are used also can have strong impacts on the use and efficacy of a reputation system. In contrast to using the average of a 5-star review system, metrics that include all transactions in the denominator of rating calculation account for buyers who do not review in a way that can adjust ratings for positive review bias (Tadelis 2016). Likewise, rather than the presentation of a single number, distributions of rankings may be displayed, which can instill confidence in the rating system. Reputation systems can also take into account a variety of factors (e.g. number of positive reviews, responsiveness to messages, consistency of review quality) and generate some sort of composite score or simply confer status to users. Merit-based status is known to encourage prosocial behavior and influence others to collective action (Simpson and Willer 2015). A system that allows users to achieve status based on a variety of scores may be another effective form of reputation system depending on context. eBay’s system gives status levels (rankings) based on total positive minus negative reviews. Airbnb’s “Superhosts” are also conferred a sort of status that may have important implications within a reputation system.

Conclusions

Reputation systems have long been central to the function of marketplaces. Indeed, they can facilitate positive experiences around economic exchange and encourage prosocial behavior. In online marketplaces, the design of online reputation systems should attempt to support intrinsic prosocial motivation and encourage honest feedback, while addressing inequalities and bias in the review process. In cases where individuals actually meet at some point in the customer journey (e.g. Über, Airbnb) a reputation may bridge online and physical communities, and can support a variety of additional interactions such as goodwill, service, and empathetic interactions. I believe that with greater understandings of reputation systems, more nuanced reputation systems will emerge that address specific UX contexts. As I propose above, increasingly sophisticated approaches may incorporate a variety of factors, rather than 5 star reviews, that can be conveyed in new rating metrics or badges of status. As more information and new UX environments emerge as well, reputation systems should evolve to better delight and drive exchange centered around prosocial behavior.

Citations

Simpson, B., & Willer, R. (2015). Beyond altruism: Sociological foundations of cooperation and prosocial behavior. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 43-63.

Diekmann, A., Jann, B., Przepiorka, W., & Wehrli, S. (2014). Reputation formation and the evolution of cooperation in anonymous online markets.American Sociological Review, 79(1), 65-85.

Tadelis, Steven. “The Economics of Reputation and Feedback Systems in E-Commerce Marketplaces.” IEEE Internet Computing 20.1 (2016): 12-19.

Fradkin, A., Grewal, E., & Holtz, D. (2017). The Determinants of Online Review Informativeness: Evidence from Field Experiments on Airbnb.

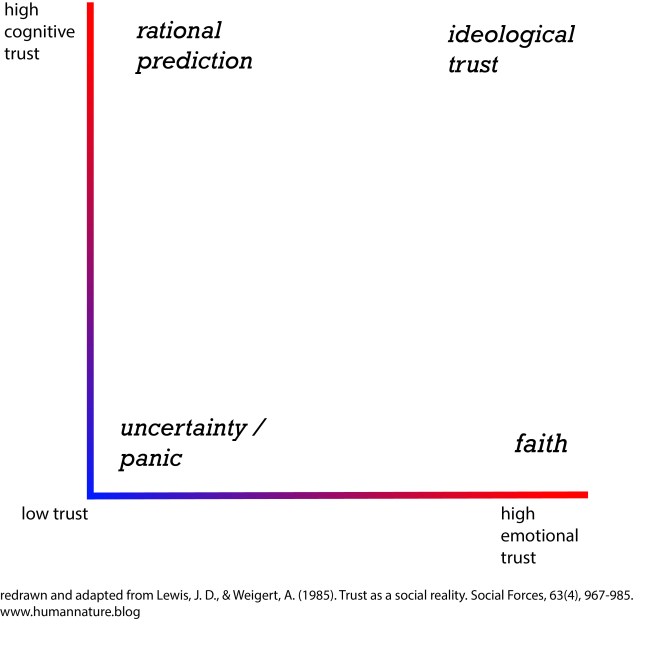

In addition, trust may act on an interpersonal or system level (Lewis and Weigert 1985). Interpersonal trust may be more prominent where personal trust is at stake and is related to close relationships of primary group interactions (and therefore stronger components of emotional trust), whereas system trust is typically accompanied by top-down rules and sanctions (Lewis and Weigert 1985). As such, designing for trust in user experiences may necessarily relate to system trust, but the visibility of such structure or the appearance of interpersonal trust may be a deliberate design consideration. For example, a social network where endorsements are portrayed as drawing on more involved interpersonal relationships and relate to the people themselves, the greater focus on emotional trust builds in an aspect of interpersonal trust to the system trust environment (e.g. LinkedIn). In contrast a reputation system that is more about the quality of a transaction directly highlights system trust for what it is and orients more around cognitive trust (e.g. Airbnb).

In addition, trust may act on an interpersonal or system level (Lewis and Weigert 1985). Interpersonal trust may be more prominent where personal trust is at stake and is related to close relationships of primary group interactions (and therefore stronger components of emotional trust), whereas system trust is typically accompanied by top-down rules and sanctions (Lewis and Weigert 1985). As such, designing for trust in user experiences may necessarily relate to system trust, but the visibility of such structure or the appearance of interpersonal trust may be a deliberate design consideration. For example, a social network where endorsements are portrayed as drawing on more involved interpersonal relationships and relate to the people themselves, the greater focus on emotional trust builds in an aspect of interpersonal trust to the system trust environment (e.g. LinkedIn). In contrast a reputation system that is more about the quality of a transaction directly highlights system trust for what it is and orients more around cognitive trust (e.g. Airbnb).